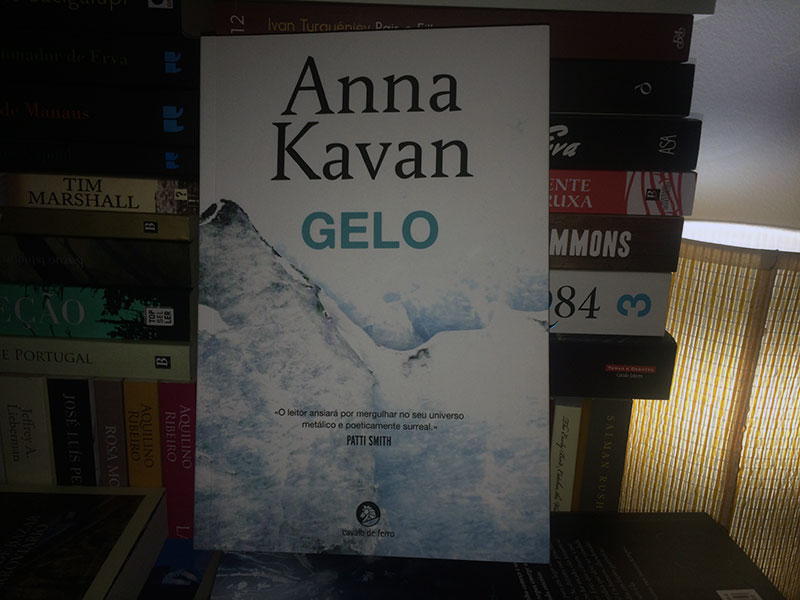

gelo de anna kavan

Num mundo dominado pela destruição, a guerra e o pânico, um protagonista sem nome vagueia por uma paisagem surreal, mas familiar, em demanda de uma estranha jovem mulher de cabelos prateados. Nesta busca insistente e obsessiva, atravessa mares e planícies geladas, ruínas de cidades saqueadas, lutando contra o tempo numa missão que tem tanto de real quanto de imaginário: salvar esta «rapariga de vidro» antes que o mundo conhecido se encerre no interior de uma muralha de gelo.

Wook

Leitura excelente que pode ser quase, mas quase resumida a este fragmento;

As minhas ideias estavam confusas. De uma forma muito peculiar, a irrealidade do mundo exterior parecia ser uma extensão do meu perturbado estado de espírito.

página 65

A história surreal confunde o leitor e faz-lo questionar o percepcionado. Lindo; realmente lindo.

Tradução de Maria do Carmo Figueira

oton lustosa

O homem não busca apenas satisfazer as suas necessidades materiais. Para viver, plenamente, busca a satisfação espiritual. Cheio de poder, posto que dotado de inteligência – esta explosiva força criadora -, o homem transforma o mundo. Escarafuncha, mexe, bisbilhota as coisas da Natureza… Queda-se extasiado diante das belezas naturais… Encafifa-se com os mistérios que levam à perfeição das coisas criadas… Chega a uma conclusão derradeira, inapelável: Deus existe! Mas… De tanto investigar termina por concluir que algo deve ser melhorado ainda neste mundo de Deus. Quer o homem o mundo ao seu serviço, útil e prático; que lhe proporcione um estado tal de bonança, inenarrável, sublime. Algo a que deu o nome de Felicidade! Eis o objetivo primeiro e último do gênero humano: Ser Feliz! Por isso transforma, modifica, cria, destrói, luta. E a tal felicidade como uma miragem, ora perto ora longe. E haja esperanças e haja angústias e haja sonhos! Ah! os sonhos!… Quer o homem, em pleno estado de vigília, entender os sonhos, torná-los concretos. Freud bem que tentou ensinar a fórmula. Mas a psicanálise freudiana, para muitos, ainda é um imenso labirinto onírico. Por isso, em perseguição dessa tão sonhada felicidade, o homem desanda a sofrer. Busca, finalmente, um lenitivo para essas dores do espírito. Põe-se a serviço da construção e da contemplação da Beleza. Nesta sua caminhada terráquea, a estação que o leva a mais se aproximar da felicidade é a contemplação da Beleza. É aí que as artes ocupam importantíssimo papel na vida do homem. Aliás, ouso dizer, sem a arte – expressão maior da inteligência humana -, o homem não passaria de um miserável bicho bípede, deslanado, sem cauda, sem garras, despreparado para a caça e para a pesca; e sem nenhuma chance de cavar, mergulhar e voar. Mas o homem, ser divino, tem a Inteligência!… Que o leva ao trabalho maneiroso, ao engenho, à arte, à perfeição, ao amor… E ainda o levará à felicidade!

Oton Lustosa

Texto extraído do discurso de posse do escritor Oton Lustosa na cadeira n° 05 da Academia Piauiense de Letras.

lol, camuflagem 10.0 – desvio

Apesar de ter criado uma história. Não a publico. Fica apenas a imagem de um lol tirolês.

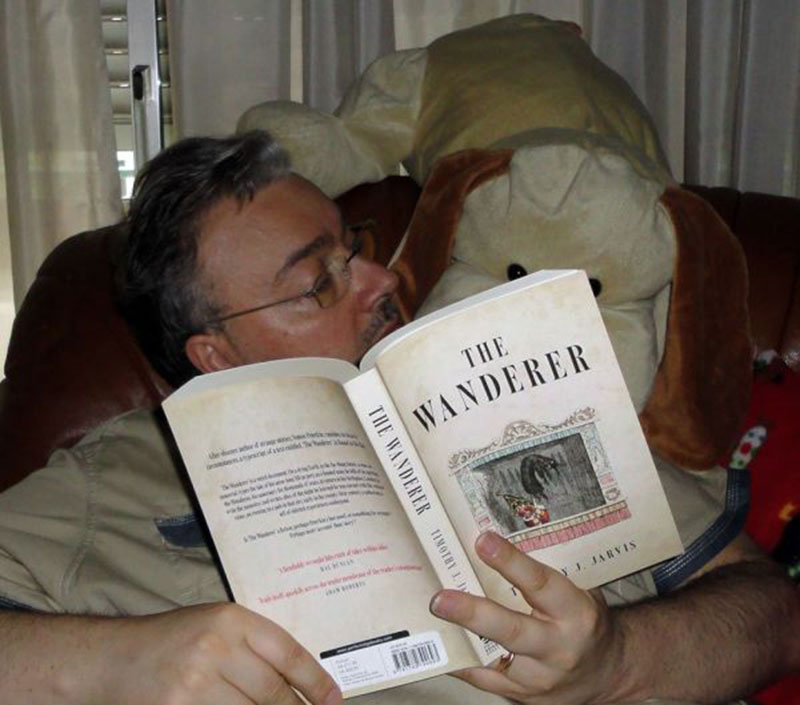

an itinerant interview to timothy jarvis

After reading the story Nae Greeance o’ Bane I need to read more words written by Timothy Jarvis so I have bought The Wanderer and I can just say for now that it is an unmatched brilliance.

About Nae Greeance o’ Bane:

I was absolutely gripped during the entire story. Nae Greeance o’ Bane by Tim Jarvis is scary, claustrophobic and even funny. I loved the pacing of this story and the way Tim Jarvis creates a bizarre situation. If it were a movie, I would say that the CGI effects were the best and that the characters of Jeff and Tommy well developed.

You have to read this story. You won’t believe how good it is.

1. Do you have a specific writing style?

I’ve used the word ‘antic’ to refer to the way I write. Antic, which combines a sense of the grotesque with the bizarre and has overtones of the archaic, seems to me to go against consistency and seriousness of tone. A dark mood and a kind of unity of affect is often prized in modern Gothic and horror writing. I’d relate this, to go back to one of the roots of modern genre, to what Edgar Allan Poe called his ‘Arabesque’ side. But I’ve always found Poe’s ‘grotesque’ or impish and darkly humorous mode just as, and possibly even more, compelling. I particularly like how, in his strange puzzle of a novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, he veers jarringly between these opposed atmospheres. In my own work, I try to shift abruptly from cloying sentiment, to excessive gore, from eldritch horror to comic absurdity.

the wanderer

I also use found manuscripts, frame narratives, and stories within stories in my work, because I want them to seep out and contaminate the world in which the reader reads, not be closed fantasies. I feel more of an affinity to the disorienting involutions of a labyrinthine narrative, than I do to strong, neat plotting, and I hope to stretch readers’ comprehension and test their patience as much as possible.

2. What books have most influenced your life?

As a child I read Alan Garner’s The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath, and was immediately struck by them. They’re so different from other children’s fantasies, there’s bleakness to them, a sense of real peril, a narrative complexity and also a profound engagement with the land, Alderly Edge in Cheshire, and its lore – the books are not a motley mix of different mythologies, but a sustained and powerful engagement with British folktale. Their sense that the fantastic is not hermetic, sealed off from the ‘real’ world, has been a profound influence on my thinking and writing. In 2012, Garner finished his trilogy with a final volume, Boneland, which portrays one of the children of the earlier books, now a grown man dislocated and disturbed, still dealing with the trauma of his encounter with the fantastic, which he has erased from his memory, but which still marks him in horrible ways. But that atmosphere is already there in the earlier books, and in Garner’s other novels from the 1960s, Elidor and The Owl Service, and it is an atmosphere that profoundly shaped my thinking growing up.

3. If you had to choose, which writer would you consider a mentor?

I’d written some tales of adventure when I was young, but didn’t think of myself as a writer, or consider that it was something I wanted to do, till I was in my early twenties. Three writers, whose work I was reading obsessively at that time, had a profound influence on the way my inchoate fiction developed: Angela Carter, whose exhilarating formal inventiveness and transmutative, yet grounded, fantastic, I still attempt to ape; M. John Harrison, whose bleak, cruel, and dreary otherworlds in the Viriconium sequence, and the novel The Course of the Heart, were a huge influence on me, and whose thoughtful poetics, expressed on his blog and in essays, continues to inspire me; and Jorge Luis Borges, whose stories, especially those in which the unreal is found at the heart of the ‘real’, I found, and still find, have a powerful hold over me.

4. What are your current projects?

I’m currently working on a portmanteau novel which tells of London falling into decay and dissolution, and of the discovery of a series of manuscripts that relate stories of city’s tutelary daemons. Another strand details the life and death of a Belgian decadent poet during the siege of Paris in 1870. These two strands are bound up together by the idea that the crises in the cities are related to the decline of their daemons.

5. How much research do you do?

I don’t, as a general rule, do much specific research; I mostly read fiction, and steep myself in the atmosphere of various stories. But I do read up on a historical period if a narrative calls for it – I think it especially important for writers of the uncanny to get details right, seed the text with believable realistic elements that jar with the fantastic parts of the narrative. And I also tend to write about places I know and to walk them before writing; my practice is not psychogeographical, though, I’m not wearing down through layers of the landscape’s palimpsest with my tramping, but seeking the kind of epiphany that is to be found in the work of Arthur Machen, when a sudden transfiguring vision is had when walking through a well-known cemetery, or looking into the mouth a familiar alley.

6. Do you write full-time or part-time?

I only write part-time (and sometimes very part-time), but I’m lucky enough that my day job is to teach Creative Writing to undergraduate students, so I’m most of the time immersed in a creative environment.

7. Where do your ideas come from?

I do a lot of free writing, writing in which my conscious mind is as little involved as possible, in an attempt to dredge stuff up from the murk of my unconscious mind. I often do this to a prompt, a line of text from another book, or an image, something of that nature. I’ll then assemble some of these fragments, throw in some other disparate things that have interested me in some way, things I’ve seen, snippets of conversation I’ve overheard, things I’ve been told, images I’ve found, and things I’ve read from both fiction and non-fiction. And then I’ll force myself to come up with ways of linking together what is usually a fairly incongruous set. I can’t come up with ideas for my fiction deliberately, consciously, so I rely on tricks like this that force my unconscious to work. When it’s going well, I sometimes feel I’m tapping into some collective cultural pool of oneiric imagery, or working some kind of transmutative alchemy.

There are two key texts behind my way of writing. The first is Raymond Roussell’s posthumously published essay, ‘How I Wrote Certain of My Books’. In this essay, Roussell partially anatomizes his idiosyncratic poetics. He describes a technique he used to generate narrative content which consisted of the manipulation of homonyms, similar sounding words. He’d take a trite phrase such as a cliché or an advertising slogan, then come up with another phrase that sounded similar, but which had a different meaning. He’d then force himself to work the meaning of the second phrase into his narrative, no matter how odd it was. And this was just an early level of his method – later stages, which he declines to discuss in the essay, were presumably even stranger. While I don’t use a method as individual or as demanding as Roussell’s, the spirit of his process has influenced mine.

The second text is Gilles Deleuze’s late essay of 1993, ‘Literature and Life’. In it, Deleuze writes, ‘The writer returns from what he has seen and heard with bloodshot eyes and pierced eardrums.’ This is an important notion for me, the idea that writing is a risky endeavour, that it involves plumbing the depths in some way.

8. How can readers discover more about you and you work?

I’ve a couple of blogs: timothyjjarvis.wordpress.com, which contains information about me as a writer, some musings, and a soundtrack for my novel, The Wanderer; and treatisesondust.wordpress.com, which is a collection of antic texts I’ve found. I’m pretty poor at updating these, but I can also be found on Twitter, @TimothyJJarvis.

clairvoyant interview to daniel mills

I had a lot of expectations before reading “Revenants: A Dream of New England”, and I must admit now that I was pleasantly surprised! A simple conclusion: if I want to know about reality I will watch the news; if I get tired, and I get tired all the time, of hearing about the “real” brutality of the world then I just need to read Daniel Mills. If this don’t makes any sense is normal, but all makes sense to me.

Thanks to Jason E. Rolfe for making me read Daniel Mills. Is an author worth following.

1. Do you have a specific writing style?

I do, I think. At least I hope so.

For me the cultivation of a unique, authentic voice ought to be any writer’s foremost concern, and the truth is I spent many years working to develop a style of my own. Only with Revenants did I come to feel as though I had accomplished this, if only in part, and even now style continues to be something of an obsession to the extent that I have come to value authenticity of voice and spontaneity of expression over mere craftsmanship.

Regrettably, it has become something of a truism among writers and writing programs that “writing for one’s self” is an essentially self-indulgent activity — a shame, really, because the reality is that none of us are going to be read or remembered in, say, 500 years’ time, so you may as well do your best to be true to your own style rather than writing to please others or (Heaven help us!) writing for the market.

Even as a reader, I find that I would much rather read a book that is stylistically distinct but flawed — singular if also imperfect — than another that is well-crafted but essentially workmanlike. I’m reminded of the dismissals we regularly encounter of HP Lovecraft’s style. There are many writers out there who would have us believe HPL is a poor writer simply because his work doesn’t “tick the boxes,” as it were, with regard to plotting, adjective/adverb use, character building, etc. I see these arguments and I think to myself: yes, but surely that’s the point? You pick up a Lovecraft story to read and you are never once in doubt about its author — the unity of style, voice, and vision is so distinctive, so complete.

Another example can be found in the novels of Walter M. Miller, JR. His first novel – A Canticle for Leibowitz – is an undisputed masterpiece while his second – Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman – was left unfinished at the time of his suicide. Saint Leibowitz was later finished by Terry Bisson and released after Miller’s death to a very muted reception indeed. Certainly Saint Leibowitz is a tortured work, one that is deeply flawed in execution, but as such, it somehow seems to contain more of Miller himself, his distinct vision of sin, grace, and redemption.

And though Canticle is unquestionably the “better” book, I have read it only once while I reread Saint Leibowitz every 3-4 years.

2. What books have most influenced your life?

Like most other readers, I have a cherished handful of books which I continually read and reread, which have become so deeply enmeshed within the fabric of my life that I would be hard pressed to qualify their influence on me in any meaningful way. Suffice it to say that I have lived in the cold snow country of Yasunari Kawabata’s novel of the same name and likewise experienced the oppressive summer heat of LP Hartley’s The Go-Between. I have witnessed the hypocrisy of Victorian society as evidenced by Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh and lay awake listening for the dead voices that haunt Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Paramo. And that’s not to mention the weeks and months I have devoted to unraveling the riddles of Charles Palliser’s The Quincunx and Rustication.

Other books that have influenced me would include Par Lagerkvist’s Barabbas, Hesse’s Demian, Miller’s Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman, Breece D’J Pancake’s The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake, Pinckney Benedict’s Dogs of God, and Isak Dinesen’s Seven Gothic Tales.

3. If you had to choose, which writer would you consider a mentor?

Lovecraft again springs to mind. Here was a man who wrote what he wanted in the way he wanted and who devoted his entire life to his art though it meant an existence characterized by near-constant poverty. Unlike Dickinson or Kafka — who might also be said to embody this artistic ideal — HPL was a man who had fallen behind his own time rather than leap out ahead of it ala Dickinson or embody it fully ala Kafka.

For this reason I cannot help but relate to the sense of poignant dislocation which so pervades his work, that yearning for a different time. Yes, his opinions on race (among other topics) are abhorrent but he was by almost all accounts a gentleman of great personal kindness, courtesy, integrity, who served as mentor to a generation of young weird/ horror writers. In many ways he was broken — it would be difficult to argue otherwise — but I’m broken too, as are we all, and for me, it is this sense of brokenness as we encounter it in his work that keeps me coming back to him.

4. What are your current projects?

I spent much of 2013 and 2014 working on a new Gothic novel addressing the American Spiritualist movement in the wake of the American Civil War. In addition to this I have continued to work on short stories, a number of which are forthcoming later this year in such venues as Aickman’s Heirs (ed. Simon Strantzas), Autumn Cthulhu (ed. Mike Davis), Leaves of a Necronomicon (ed. Joseph S. Pulver, Sr) and Nightscript I (ed. C.M. Muller).

5. How much research do you do?

A bit of a difficult question. I’ve mentioned my own feelings of dislocation and general disaffection with modern society — “I just wasn’t made for these times” as Brian Wilson has it — and the sad fact is that I spend altogether too much time fetishizing the past, whether that’s devouring Victorian novels or old religious tracts or haunting the historic houses and graveyards of Vermont. In other words: the research is always ongoing if only for the simple reason that I don’t think of it as “research.”

For example I’ve lately become obsessed with the lives of Horatio Spafford and Philip Bliss, who wrote the words and music, respectively, to the well-known 19th century hymn “It is Well with my Soul.” Spafford was moved to write the words following the loss of his four daughters in the wreck of The Ville de Havre — one of the great calamities of its day — and Bliss later supplied the music mere months before his own tragic death in the Ashtabula River Rail Disaster. Will I ever do anything with this? Probably not. All the same it is fascinating.

6. Do you write full-time or part-time?

Part-time.

7. Where do your ideas come from?

I believe in genuine inspiration — or “the muse” as it’s traditionally understood — but I tend to see it as an ongoing process rather than any kind of epiphany. Routine is important. During the course of each day I try to make time for the things that fascinate and move me. This could mean a walk in the woods or an undistracted hour spent listening to music or even just twenty minutes of stolen reading time on my daily commute to work. In this way I try to make a habit of beauty in all things so that I’m charged with inspiration when I sit down to work. I don’t always succeed at this, of course, and Lord knows I’m as bad as anyone else at making time for writing, but this way at least I don’t have to worry about feeling inspired.

8. How can readers discover more about you and you work?

You can find me online at http://www.daniel-mills.net where I maintain a bibliography and blog or find me in the usual places: Facebook, Goodreads, etc. If you happen to live in the USA, there’s a good chance you can find my novel Revenants at your local library. Similarly you can try to track me down in person at Readercon or this year’s Necronomicon in Providence, RI.